Dies ist eine überarbeitete Abschrift des 1859 (ursprünglich 1852) erschienen Buches, “PURSUIVANT OF ARMS” von James Robinson Planché (siehe https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_Planch%C3%A9#Heraldic_career und https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_Planché).

- Prefaces and summaries

- PRELIMINARY OBSERVATIONS.

- THE ORIGIN OF HERALDRY.

- THE SHIELD,

- METALS, TINCTURES, AND FURS.

- THE HONOURABLE ORDINARIES,

- NATURAL AND ARTIFICIAL OBJECTS

- MARKS OF CADENCY,

- BLAZON

- MARSHALLING.

- ABATEMENTS AND AUGMENTATIONS.

- CRESTS AND SUPPORTERS.

- SUPPORTERS

- BADGES.

- CONCLUSION.

- INDEX TO HERALDIC TERMS AND FIGURES.

- INDEX TO NAMES OF PERSONS &c. WHOSE ARMORIAL BEARINGS ARE ENGRAVED OR DESCRIBED.

- APPENDIX.

- Footnotes

- All the pictures in a gallery

THE PURSUIVANT OF ARMS.

THE

PURSUIVANT OF ARMS;

OR,

HERALDRY FOUNDED UPON FACTS.

BY

J.R. PLANCHÉ, ROUGE CROIX.

“My attempt is not of presumption to teach (I myself having most need to be taught), but only to the intent that gentlemen who seek to know all good things and would have an entry into this, may not find here a thing expedient, but rather, a poor help thereto.” – Leigh’s accedence of armorie.

NEW EDITION.

WITH ADDITIONS AND CORRECTIONS.

LONDON: ROBERT HARDWICKE, 192, PICADILLY.

AND ALL BOOKSELLERS.

1859

Prefaces and summaries

To

SIR CHARLES GEORGE YOUNG, KNT.,

GARTER KING OF Arms,

&c. &c. &c.

DEAR SIR CHARLES,

I have much pleasure in inscribing this little volume to you.

A personal acquaintance of nearly five and twenty years might, of itself; have entitled me to the privilege of thus expressing my respect for an able antiquary, and esteem for a worrying man, but as Garter King of Arms, you have a double claim to this trifling tribute, independently of that of private friendship: Firstly, as the principal officer of a Corporation to which my best thanks are due for the courtesy of all, and the assistance of many of its members. Secondly, as one of that body, most competent to judge of the difficulties which beset the study of Heraldic Antiquities, and the real value of the results of such labour. For the latter reason also, I have less hesitation in dedicating to you a necessarily imperfect performance, as your experience will dispose you to excuse, at the same time that it may enable you to correct me.

You are aware I have a theory, and I believe are not quite as satisfied as I am of the soundness of its foundation; but I know that we are equally anxious for the establishment of any facts which may tend to elevate the Science of Armory, and render its study as useful as its devices are acknowledged ornamental.

I trust you will feel in the perusal of these pages, that, however naturally desirous to prove the truth of my position, I have not wilfully strained a point to bolster up an opinion; and that in any strictures upon those writers who have contributed to the mystification and degradation of Arms, I have only been actuated by a sincere desire to uphold the true dignity of the office of Herald, and vindicate a science which I believe has been undervalued because it has not been understood.

Believe me,

DEAR SIR CHARLES,

Your very sincere and obliged

J. R. PLANCHÉ.

Brompton.

PREFACE TO NEW EDITION.

“WHEN I said I would die a bachelor, I did not think I should live tilt I were married,” exclaims Benedict; and most assuredly, when I styled myself a Pursuivant of Arms by my own creation, I had little idea that I should so soon have the honour to become one, “de jure et de facto.”

The copyright of this book having passed into other hands, and a fresh issue being determined on, I have gladly seized the opportunity of correcting some inadvertencies and typographical errors, supplying omissions, and adding such information as I have gathered during the six years which have elapsed since its first publication. The favour with which it was then received by the Press has rendered this revision a grateful task; and my acknowledgments are especially due to the writer of the notice which appeared in the Journal of the Archaeological Institute for March, 1852, for the kind spirit in which he called my attention to the deficiencies, as well as for the very high encomium he bestowed upon the general character of the work. In the notes and illustrations now appended to The Pursuivant, I have gladly availed myself of his suggestions, and endeavoured to answer some of his inquiries, earnestly desiring, for the sake of literature, that every author could meet with so competent as well as so courteous a critic.

J.R. PLANCHÉ, Rouge Croix.

College of Arms.

PREFACE TO THE FIRST EDITION.

READER, commonly called courteous or gentle Reader. I am a Pursuivant of Arms, – extraordinary, being of my own creation, – not vain enough to fancy myself a Herald, nor visionary enough to hope I shall one day become a King. The doors of the College open to me as a harmless enthusiast, not as a worshipful member. I have no tabard to my back, no crown to my brows, no authority, no office: I am guiltless of grants and unacquainted with fees; but I am devoted to the study of Heraldry, and may truly call myself “a pursuivant of Arms,” as I have long and diligently pursued the subject by a path, untrodden I believe by others, though several have crossed the track. Are you inclined to keep me company and see whither it will lead us? For the end, I tell you fairly, is yet to seek. If so, have with you. I will guide you as well as I can, and as far as I know. No great distance, perchance; but I will rather declare my ignorance than wilfully misdirect your steps, for I look upon our journey as one in quest of Truth; and he would ill deserve to find her, who should lie by the way.

LIST OF WOOD-CUTS.

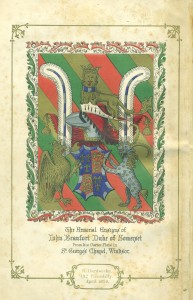

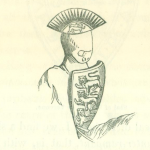

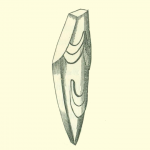

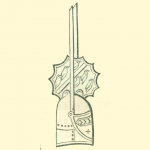

FRONTISPIECE, TO FACE TITLE.

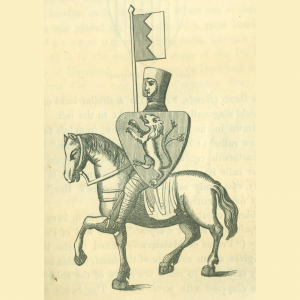

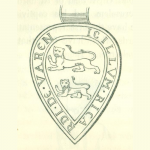

THE Garter Plate of John Beaufort, Earl of Somerset, afterwards Dupe of Somerset and Earl of Kendal. Elected 20th of Henry VI. This is the earliest Garter Plate with supporters, and has been selected as affording a fine example of a complete achievement in the first half of the fifteenth century.

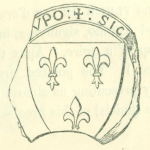

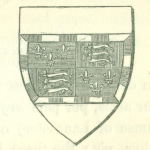

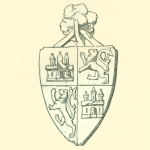

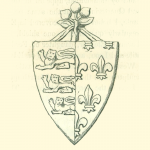

ARMS Quarterly, France and England, a border, gobony or compony, argent and azure.

Cam. A lion, statant regardant, and ducally crowned, or, gorged with a collar, compony, same as the border of the arms.

SUPPORTERS. Dexter, an eagle ducally crowned, or. Sinister, an ibex or antelope, argent. Bezanté, attired, hoofed, maned and tusked, or.

TEE HELM. Or, with MANTLING of crimson velvet, on which may be distinguished two sprigs of trefoil. On either aide, in pale, a large ostrich feather, argent, quilled, compony as the border of the arms.

The whole upon a field, bendy, or, gules, and vert, and bordered with foliage.

PRELIMINARY OBSERVATIONS.

HERALDRY has been contemptuously termed “the science of fools with long memories.” There is more wit than wisdom in the remark, and with the many, a smart saying has unfortunately a great advantage over a just one. The absurd fancies of writers, who have furnished even Adam with a coat of arms, and would give as many quarterings to Noah as might satisfy a Count of the Holy Roman Empire, are fit subjects for ridicule; but the abuse of an art can never, amongst thinking men, lessen the use of it; and until all respect for high and noble deeds shall be destroyed on earth, an art which assists to perpetuate the remembrance of their enactors can never truly be called “the science of fools.” Heraldry is the short-hand of History. In its figures, properly interpreted, we read the chronicle of centuries. If a knowledge of History be a desideratum in the education of youth, surely nothing that tends to facilitate its acquirement and increase its impression can be considered vain or worthless. In place of branding Heraldry as the science of fools, ought we not rather to consider it as one which, properly directed, may render even fools wise? Would not a general knowledge of the arms of our principal ancient English families form a sort of artificial memory for the young student of English History, and give additional interest to the details of the deeds of those who bore them: of events in which the founders of those families were actors? The funeral escutcheon, the passing equipage, the monumental tablet, would they not in return daily, almost hourly, recall to his mind the history of those who first assumed or acquired the devices thereon depicted? Such an opinion is, I rejoice to say, gradually becoming general. Indeed, it was the frequent inquiry of parents “Can you recommend me a work on Heraldry ?” which induced me to imagine, that one founded on facts alone, might find favour in the eyes of those who desire truth above all things, and who, to speak the truth, are the only persons I ever had much care to please. Disclaiming, therefore, all intentional offence to previous writers on these much-vexed questions, I start with the declaration that as I have implicitly believed nobody, I desire not that any one should blindly credit me; but form his own conclusion from the evidence I may succeed in producing; rating mere speculations (for he will find some of my own) at their lowest value. And now, having made my profession of, anything but, faith, let us begin at the beginning by ascertaining if possible where that beginning may begin. Certainly not quite so early as the ingenious Sylvanus Morgan would have us believe, in his anxiety to prove Adam a gentleman, nor with the reign of Alexander the Great, notwithstanding Sir John Ferne quotes Aristotle in support of his assertion, nor in the times of Caligula or Vespasian as, even the learned Camden says, may perhaps be inferred from the expressions of Suetonius. There can be no doubt that nations as well as individuals have from the earliest periods been distinguished by particular ensigns: but the bundles of hay borne by the followers of Romulus might as properly be called the arms of Rome, as the silver eagles that succeeded them. To come at once to the point. Have we any direct testimony to the existence of armorial bearings in the accepted sense of the terra, earlier than the 12th century, when they seem to have been adopted with one accord throughout Europe? Previous to that period we read of “white shields” and “red shields “and “gilded shields.” In Saemund’s Edda, mention is made of a red shield with a golden border. The Encomiast of Emma, speaks merely of the glittering effulgence of the shields suspended on the Bide of the vessels of Canute. In the Anglo-Saxon illuminations we perceive the shields of warriors generally painted white, with red and blue borders and circles: on those of our Norman invaders, as represented in the Bayeux Tapestry, a work, at the earliest, of the close of the 1 lth century, we find crosses, rings, grotesque monsters, and fanciful devices of various descriptions, but nothing approaching a regular heraldic figure, or disposition of figures.1

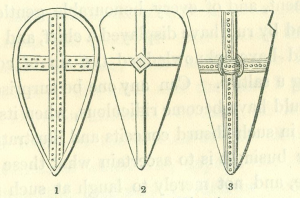

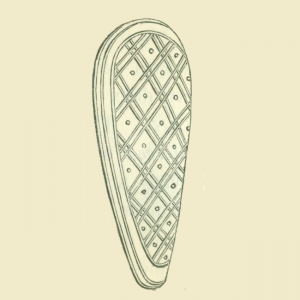

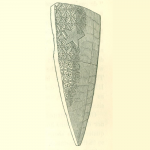

Anna Comnena, in the life of her father Alexius, thus minutely describes the shield of the French knights at this period. “For defence they have an impenetrable shield, not of a round but of an oblong shape, broad at the upper part and terminating in a point, the surface is not flat but convex, so as to embrace the person of the wearer and the exterior face is of metal so highly polished by frequent rubbings, with an umbo (boss) of shining brass in the middle, as to dazzle the eyes of the beholders.” Here is the strongest possible contemporary evidence that at this period (1081 – 1118) the shields of the mort chivalric nation of Europe presented a face simply of polished metal. Robert of Aix, who was also present at the first crusade (1096 – 1101) though he speaks of the shields being resplendent with gold and gems, and painted of various colours, makes no mention of Heraldic devices.

The curious Spanish MS., recently acquired by the British Museum, executed in the monastery of Selos, diocese of Burgos, and completed in the year 1109, presents us with round shields, plain and ornamented, but nothing approaching to armorial bearings.

The shields of the leaders of the second crusade represented in the famous painted windows of the Abbot Suger, formerly in the Abbey of St. Denis near Paris, and executed of course after 1147, were also, if we may trust the engravings of them in Montfaucon, for the originals have, alas, disappeared, devoid of Heraldic insignia. The third crusade began in 1189, when Heraldic devices had already made their appearance. The seal of Philip I, Count of Flanders, of the date of 1164 is the earliest unquestionable example, in the collection of Vredius, on which the lion appears as an heraldic bearing. His cylindrical helmet is also emblazoned with a demi-lion rampant, whilst the seal of the same Count, to a document of the date 1157, as if on purpose to mark the circumstance more strongly, is without any device. Of this same period, the latter half of the 12th century, are the Heraldic Fleur-de-lys of France, and the Lions or Leopards of England.

Yet in the face of these facts, some of the most learned and laborious of our heraldic writers, have gravely furnished us with the arms not only of the Anglo-Saxon monarchs, but of a long line of British Kings, as visionary as those in Banquo’s glass, up to Brute or Brutus, the fabled grandson of Aeneas, who wandering in Bretagne in France, fell asleep, and on waking found an ermine upon his shield, whence we are requested to believe the Dukes of Britanny derived their arms: and not contented with giving this story as a legend, Sir George Mackenzie states it as an historical fact, and says “from that time Brutus wore a shield ermine.” What credit then can we give to a writer who invents or propagates so gross a falsehood? How can we believe upon his unsupported authority, statements which have not even possibility in their favour? The most extravagant of these fancies have been exposed, or passed over in silence, by later writers: but to a more early existence of Heraldry than I have yet found authority for, some even in the present day cling with great pertinacity.

THE ORIGIN OF HERALDRY.

Notwithstanding all the ink that has been shed, and all the learning that has been displayed in the controversy, the origin of Heraldry is still but conjectural, its first resolution into a science without an authenticated date. It has been attributed with the almost general consent of every rational writer on the subject, to the necessity for distinguishing the principal leaders during the crusades, and the conjecture is natural enough, when we consider the confusion likely to have occurred through the junction of so many powers on the plains of Palestine – the commingling of all the streams of chivalry, that flowed by every channel from every part of Europe into Asia during the holy wars. Still it is but a conjecture, and if a correct one, it may first be asked, how is it that so important and remarkable a circumstance should be unrecorded by the minute chroniclers and veracious painters of the times, to whom from their peculiar tastes and habits, it must have been as interesting as it was novel ? But there is a still greater obstacle to the reception of that hypothesis in the fact, that the evidence of the best authorities of that period, which have survived to us, both writers and painters, goes directly in disproof of any such science or practice existing at least during the two first crusades, and the third did not commence till the year 1189, before which period, as I have stated, heraldic devices had already made their appearance. At the same time, be it fully understood that, although not a believer to the same extent as many, in the round assertion, unsupported by any contemporary authority as yet discovered, that Heraldry owes its origin to the crusades, I by no means dispute the influence of those expeditions upon the dawn of it; as it would be impossible to look upon the bearings of our ancient nobility, or upon any treatise upon armory, without being struck by the emblems of holy warfare and pilgrimage, the traces of Oriental language and the representation of natural and artificial objects of Asiatic production. I simply confine myself to the fact, that an authenticated date for the origin of Heraldry, or, to speak more strictly, armorial bearings, has yet to be discovered.

Let us first examine what are the materials we possess for its History and illustration. Our earliest heraldic information is derived, at present, from a copy made in 1586 by Glover, Somerset Herald, of a roll of arms of the reign of Henry III,2 that is to say a list or catalogue of the arms borne by the Sovereign, the Princes of the blood, and the principal Barons and Knights of England, between the years 1216 and 1272, the original having unfortunately disappeared. The arms are not drawn; but only blazoned, the term used by Heralds for verbally describing the figures and colours in a shield, (see under BLAZON). This roll, therefore, for the authenticity of the copy was not doubted by Sir Harris Nicolas, who considered the original compilation to have been made between 1240 and 1245, furnishes us with a multitude of examples of the earliest regular armorial bearings of our Anglo-Norman nobility, blazoned correctly, and comprising nearly el the principal terms in use at the present day. Heraldry had become a science and arms hereditary. For brevity as well as distinction, I shah call this document “Glover’s Roll.”

In a volume of MSS. in the Harleian collection, British Museum, numbered 6589, is the copy of another roll of the same period, i.e. the middle of the 13th century, in which the arms are drawn in pen and ink (tricked as it is called), by Nicholas Charles, Lancaster Herald in 1607, from the original, which he states in a note, was lent him in that year “by Mr. Norry” (Norroy King of Arms). It contains nearly seven hundred coats, and is exceedingly valuable for the ancient forms of some of the charges delineated. This document I shall distinguish as “Charles’s Roll.”

The Roll of Kaerlaveroc is an Heraldic Poem in old Norman French, recounting the names and arms of the Knights at the siege of Kaerlaveroc Castle, with Edward I, A.D. 1300. From the incidental observations of the writers we gather a fund of information respecting the ancient usage of bearing arms, which in some important points differed exceedingly from the modern. This Roll has been published with valuable remarks by the late Sir Harris Nicolas.

Copies of Rolls are to be found in the College of Arms, and at the British Museum of “the Knights with Edward I, at the Battle of Falkirk;” (that one in the Harleian Collection, 6589, having been taken out of the Treasury Chamber in Paris, where the records were kept in the year 1576,) and of those who were at the Tournaments at Dunstable, 2nd of Edward II, 1309. An original roll of arms of the reign of Edward II, nearly of the same date as the last (1306 – 1314) is preserved in the Cottonian Library, British Museum, marked Caligula A. XVIII, and, one of the names and arms of those slain at Boroughbridge, 15th of Edward II, (1 321) in the Ashmolean MSS. Oxford, No. 731.

Copies of Rolls of the time of Edward III, and of Richard II, have been published by Sir H. Nicolas and Mr. Willement; and the arms of the Knights who were with Edward III, at the siege of Calais by Mr. R. Mores.

But up to this period, the close of the fourteenth century, we are without any work explanatory of the science, except a short treatise in Latin, entitled “Tractatus de Insigniis et Armis,”written by Doctor Bartolus de Saxoferratus,” (Sassoferrata) about the year 1353, and published by Sir Edward Bysshe in 1654.

A work in Latin by a writer styling himself Johannes de Bado, or de Vado Aureo, presumed to be one John of Guildford, and who acknowledges himself indebted to his master Franciscus de Foveis, or François des Fossés, is the earliest systematic treatise I have seen. It appears by the preface to have been written during the reign of Richard II, as he states it to have been compiled expressly for the late Queen Anne, Richard’s first wife, who died A. D. 1394. The arms of France, being blazoned with only three fleurs de lys, shows the work to have been completed after the reduction of the flowers to that number by Charles VI, father of Richard’s second Queen, Isabella. It was published by Sir Edward Bysshe in 1654, in conjunction with the more elaborate and better known treatise, also in Latin, by Nicolas Upton, a Canon of Salisbury and Wells, who wrote about 1441; and a translation, or rather paraphrase of a portion of Upton’s work called The Book of St. Albans, printed in 1486, completes the slender list of what may be called contemporary authorities; for with the decline of chivalry commenced the corruption of heraldry, and its officers first incorporated by Richard III, in 1483, in little more than a century, saw their science ridiculed and their authority defied. Its downfall was accelerated by the pedantic nonsense of Leigh, Morgan, Ferne, and other such writers. Camden, truly called the learned, being left almost “alone in his glory” by the herd of affected and bombastic armorists, for whom no tale was too idle, no fable too preposterous.

Had half the ingenuity and industry been exerted to discover the real origin of Armorial Insignia, which has been wasted upon inventing stories to account for them, what service might have been rendered to history, what light thrown upon genealogy and biography 1 How many a document has disappeared, or utterly perished, which was accessible to the authors of the 16th and 17th centuries, who have used their pens but to mystify or disgust their readers. Their absurdities are tempting game, but they have been recently run down by Mr. Lower, of Lewes, in his amusing work “The Curiosities of Heraldry,” and I must limit my notice of them to a brief exposure of the most mischievous, as they arise before us.

I have shown you that we have no systematic treatise to guide us of an earlier date than the close of the fourteenth century – Two hundred years after the general adoption of armorial ensigns throughout Europe! In that treatise no authorities are quoted – all is assertion unsupported by a shadow of evidence, and consequently only valuable to us as an illustration of the belief then prevalent, and of the practice of bearing arms at that period. We must, therefore, found our observations on facts discoverable amongst much earlier documents. – The armorial bearings themselves, handed down to us impressed on the seals of the Anglo-Norman nobility, (of which a valuable collection exists, appended to the duplicate of the letter of the Barons of England to Pope Boniface VIII, in the reign of Edward I, A.D. 1301) – the pictorial and sculptured decorations they bequeathed, and time has spared to us, and the incidental allusions contained in the general literature of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries.

The word Heraldry is on my title page, and I shall continue to use it in compliance with modern custom, but as I have before remarked, it is not strictly the proper name for the subject we are discussing. ARMORY, is the word used by many of our early English writers and with much more propriety. The regulation of Armorial bearings (Armoiries, French,) being only a portion of the office of the Herald, the science of Heraldry including the knowledge of every duty devolving on such an officer – namely, the marshalling of processions and conducting, the ceremonies of coronations, installations, creations of peers, funerals, marriages and the proclamation of war or peace – and during the middle ages, the bearing of letters and messages between royal and knightly personages, whether of courtesy or defiance. The superintendance and registration of trials by battle, tournaments, joustings and all chivalric encounters. The computation of the dead after conflict, and the recording of the valiant achievements of the fallen or the surviving combatants. The origin even of the name of Herald is hotly disputed. Its most probable derivation appears to be from the Greek ?? (the Fecialis of the Romans) whose functions were in many respects identical with the Herault or Heraut of the French. But the word heraldus, as applied to an officer of arms, has not yet been discovered in an earlier document than the Imperial Constitutions of Frederick Barbarossa, A.D. 1132, nearly coeval with the first indications of Armorial devices.3

The most laborious research – the most patient investigation has failed as yet in producing an authority for a truly called armorial bearing in England previous to the second crusade, A.D. 1147. But devices of rude execution and capricious assumption were undoubtedly in use amongst the Normans, as we find not only by their shields in the Bayeux Tapestry; but by the Anglo-Norman poet, Wace, who intimates that the fashion was peculiar to them. “They had shields,” he says, “on their necks and lances in their hands, and all had made (or adopted) cognizances,4 that one Norman might know another by, and that none others bore; so that no Norman might perish by the hand of another, nor one Frenchman kill another.” And this important assertion is supported by the fact, that in the Bayeux Tapestry before mentioned, the shields of the invaders alone display the figures of animals, those of the Saxons being simply ornamented with borders or crosses. I must also call your attention to the circumstance that Wace wrote this poem in the time of Henry II, whose reign commenced in 1154, and had regular armorial bearings been at that period in existence, he could scarcely have refrained from alluding to their derivation from the barbarous devices of the Norman invaders. In the eleventh and twelfth centuries we find, therefore, mention only of “devises” or “cognoissances;” but such ensigns having been adopted by warriors, and to decorate the shields and banners they bore in battle, we soon find the term “arms” applied to them, and the expression “il porte,” “he bears” such or such arms. The fashion of embroidering them on the surcoat of silk or other rich material worn over the hauberk or coat of mail, which became general during the thirteenth century, introduced the well known terms, “a coat of arms” and “coat armour,” the other familiar word, “escutcheon,” being derived from the French écusson, a shield of arms, in distinction to écu, which simply signifies a shield, whether plain, sans devise, or chargé, charged, with one or more figures or devices. Let us begin therefore with

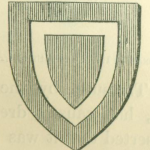

THE SHIELD,

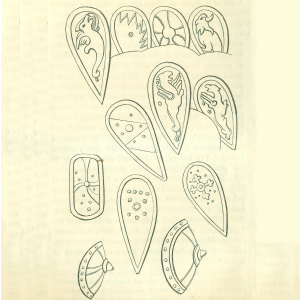

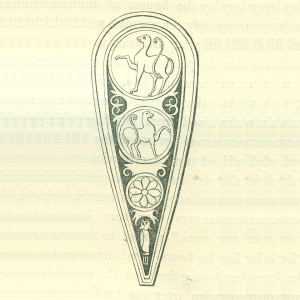

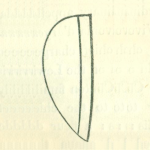

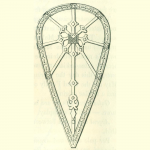

and ascertain its form about the period when it was first decorated with armorial devices. The shields of the Normans have been compared to a boy’s kit,e, and are supposed to have been assumed by them in imitation of the Sicilians, as fifty years before the conquest of England, Melo, the chief of Barri, furnished them with weapons and twelve years afterwards they conquered Apulia. A comparison of the shields in the Bayeux Tapestry, and on the early seals of the Anglo – Norman barons, with those of some Sicilian bronzes in the collection of the late Sir S. Meyrick, leaves little doubt of the fact: but before it became adorned with regular armorial bearings it had been considerably shortened, and instead of being flat was more or less bent round, till in some instances it was nearly semi-cylindrical, so that, if properly drawn or engraved, not above hall* the ornaments upon it would at times be visible. I would have you bear this fact in mind, as it is important to future illustrations. But the heraldic shield when engraved for impression, on the secretum or counter seal of the owner, was of course represented flat, that the entire arms should be seen; and as early as the reign of Henry III, it assumed the triangular or heater shape, which greatly influenced the disposition of the figures.

Our second inquiry must be concerning the colours of the Ground or Field of the shield, le Champ, which more early divided into three classes; namely,

METALS, TINCTURES, AND FURS.

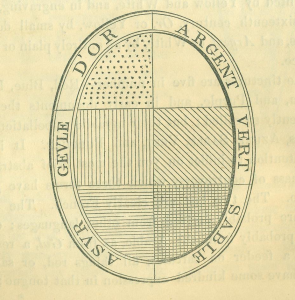

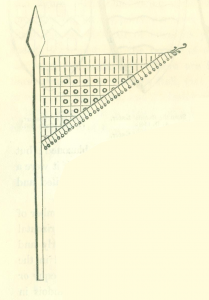

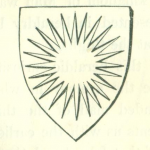

The metals are Gold, termed OR, and Silver, ARGENT, from their common names in French; -in painting represented by Yellow and White, and in engraving, since the sixteenth century, Or, or Yellow, by small dots or points, and Argent, or White, by an entirely plain or blank surface.

The tinctures are five in number-Red, Blue, Black, Green, and Purple, and in early documents they are frequently so called; but their heraldic appellations are

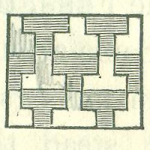

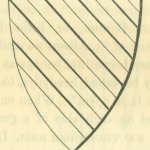

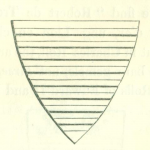

GULES, AZURE, SABLE, VERT, and PURPURE. It is not my intention to inflict on you the most brief abstract of the mass of controversy which these terms have given rise to. The two last are clearly French. The three first are probably derived from other languages; Gules most probably from the Arabic, as from Gul, a rose, to Ghia, a feeder on carcases, all things red, or sanguinary, have some kindred expression in that tongue; but I have no fact to offer in evidence, and will not waste your time in discussing the mere speculations of others. Gules, or Red, is expressed in engraving by perpendicular lines; Azure, or Blue, by horizontal lines; Sable, or Black, by perpendicular and horizontal lines, crossing each other; Vert, or Green, by diagonal lines from right to left; and Purpure, or Purple, by similar Lines from left to right. This useful mode of indicating colour is said to have been the invention of an Italian, Father Silvestre de Petra Sancta; and the earliest instance of its application in England, the engraving of the death-warrant of Charles I, to which the seals of the subscribing parties are represented attached. The annexed arrangement of. examples (Purpure omitted) is engraved from Sir Edward Bysshe’s edition of Upton, before quoted, date 1654.

FURS.

The Furs appear anciently to have been but two, ERMINE and VAIR.5

Ermine is well known, and is tolerably represented in heraldry by black spots on a white ground. Here are two examples, No. 1 being the most ancient and most natural.

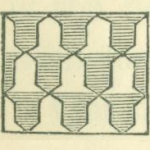

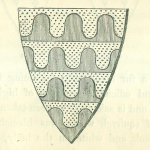

Vair was a fur much used for lining the mantles of noblemen and official personages of high rank in the middle ages, and is said to have been taken from a species of squirrel, which was blueish grey on the back, and white on the belly, and called in latin varus on that account.

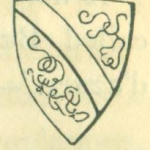

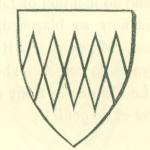

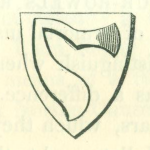

In heraldry it is now represented by shield, bell, or cup-shaped figures, blue and white alternately, ranged in horizontal rows, so that the base of the white one rests on the base of the blue. If the Vair was of any other colour and metal it was specified; as, for instance, the arms of the Earl Ferrers are blazoned in Glover’s roll, “VERRÉE de or et de goules,” and those of his brother Hugh (who according to the same authority bore vair also) are, to ensure correctness, blazoned “VAIRÉE de argent et d’azur,” which would not be necessary under other circumstances. The original form of the vair was less precise both in the outline and arrangement. Here is an example from the copy of a roll of Edward the First’s time of the arms of the Earl Ferrers above mentioned. See also the cross pattée vair of the Earl of Albemarle, p. 28.

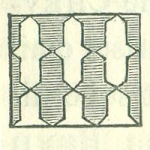

In the course of time the necessity for distinguishing the continually encreasing number of coats introduced six or seven other varieties of Furs, viz. ERMINES, or as the French more correctly term it, contre-ermine, the field being sable and the spots argent; ERMINOIS, the field or and the spots sable; ERMINITES, the same as ermine, but with a red hair on each side of the black spots; PEAN, the field sable and the spots or; VAIR EN POINT, when the point of one vair is opposite to the base of another; COUNTER-VAIR, when those of the same tincture are placed base against base, and point against point; and POTENT COUNTER-POTENT, in which the field is filled with crutch-shaped figures, counter placed like those of vair;

Potent, being an obsolete word for crutch. All these varieties of vair are understood to be composed of argent and azure if not specially blazoned otherwise.

- Counter Vair.

- Potent Counter Potent.

One of the most important rules in heraldry, and which has evidently existed from its commencement, is the interdiction against putting colour upon colour, or metal upon metal. The reason is obvious; distinctness was the grand and primary object of armorial bearings, which were intended to announce the owners as far as the eye could reach. The egregious absurdity of considering that certain tinctures typified the virtues or dispositions of the bearer, requires no other refutation than the contradictory assertions of the pedantic essayists themselves.

Our next step I think should be to ascertain as far as possible the derivations of the earliest armorial bearings, which became hereditary, and have descended to the present day, under certain heraldic appellations.

Putting aside, therefore, for the present, the figures of animals and well known natural objects, respecting which there can be no dispute, I will at once proceed to those which have received from later heralds the affected appellation of

THE HONOURABLE ORDINARIES,

so called, it would appear, from such bearings being the most ancient, as well as the most common, amongst the various cognoissances, which ultimately became hereditary. They are nine in number, the CROSS, the SALTIRE, the CHIEF, the PALE, the BEND, the FESS, the CHEVRON, the PILE and the QUARTER. Some armorists omit the pile and the quarter, classing them amongst subordinate ordinaries, and place in their stead the BEND SINISTER and the BAR; but as the two latter are merely varieties of the bend and the fess, I prefer the enumeration above-mentioned. Of these, all but the pile, we can find traces in the shields of the eleventh and twelfth centuries, on which they appear, not as armorial ensigns, but as the necessary wooden or metal strengthenings of the shields themselves, in some instances more ornamental than in others, and no doubt gilt, silvered, or painted in the gayest colours, according to the fancy of the bearer.

This, however, was much too simple a fact for the writers on heraldry, or perhaps the heralds themselves, and the most absurd as well as contradictory meanings have been attached to each of these figures, some fanciful authors asserting that they represented the various habiliments of a knight, as for instance, the chief, his helmet; the saltire, his sword; the pale, his spear; the bend, his scarf; the fess, his girdle, and the chevron, his spur! Others that they were symbols of the crucifixion, including the lance, which pierced the side of the Saviour, the nail which fastened his feet, &c., whilst others again contend that they typified certain ranks or qualifications. The chief, says Leigh, signified “a senator or honourable man,” and, following Upton, he tells you that the saltire was an engin to take wild beasts, and therefore given to rich or coveteous people, such as would not easily depart from their substance.” I need scarcely point out that had such been the facts, the shield of every baron summoned to parliament, and of every honourable gentleman, must of right and by rule have displayed a chief, and that few, if any, would have acknowledged the sin of covetousness by bearing a saltire. Can any one be surprised that heraldry should have become ridiculous, when its professors luxuriated in such absurd conceits and illustrations.

But our business is to ascertain what these ordinaries really were, and not merely to laugh at such phantasies. To begin then with

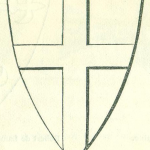

The CROSS: admitting that nothing was more common in the early days of Christianity than to paint crosses of different forms upon the shield, or embroider them on the standard, and that numerous instances may be produced from illuminated manuscripts previous to the Conquest, the Bayeux Tapestry, and other authorities, of such a practice being continued to the period when heraldry burst upon the chivalric world in its full glory; most of the peculiar crosses which form regular heraldic figures are to be traced to the metal clamps or braces required to strengthen and protect the long kite-shaped shield of the eleventh and twelfth centuries. Leaving however the varieties to be illustrated under their proper heads, I will merely point out to you some early examples of the PLAIN, or ST. GEORGE’S CROSS as this ordinary is always understood to be. They occur on the shields of a set of chessmen of the twelfth century, discovered in the Isle of Lewis, and engraved in vol. xxiv of the Archaeologia, with a most learned and elaborate description by Sir Frederick Madden.

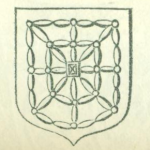

No. 1 presents us with a plain cross composed of four narrow pieces of wood or iron, two being perpendicularly and two horizontally nailed or rivetted close to each other, (the heads of the nails or rivets plainly appearing) the outer edge of the shield being defended by a border, no doubt of metal.

No. 2 exhibits a plain cross, apparently of metal, fastened in the centre by a nut or plate pierced in the centre, and forming what heralds call a mascle.

No. 3 displays a richly ornamented cross, the transverse pieces being interlaced and surrounded by a ring, in heraldry termed an annulet. It is surely impossible to examine these shields and not to admit that the holy symbol of redemption was peculiarly adapted by its form to give strength to them, and to rivet or clamp together the double layers of boards, of which, according to existing evidence they were composed.

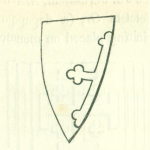

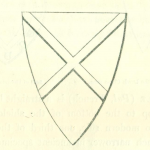

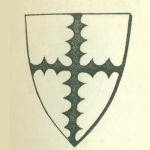

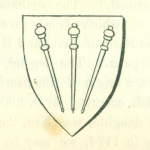

As an heraldic example here is the coat of John de Boun (Bohun), from the Roll, temp. Ed. I.

The earliest varieties of this ordinary are the

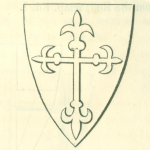

- Cross FLEURY, FLORETTÉE or FLURTY,

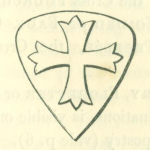

- the Cross PATONCÉE,

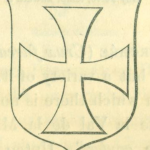

- the Cross PATÉE,

- the Cross FOURCHÉE,

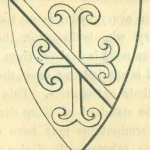

- the Cross MOLINE,

- the Cross VOIDED or FAUX CROIX,

- the Cross BOTTONNÉE or TREFLÉE,

- the Cross POMETTÉE or BOURDONÉE.

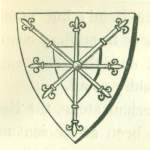

The Cross FLEURY, FLORETTEE or FLURTY, so called from its floral terminations, is visible on one of the shields in the Bayeux Tapestry (vide p. 6). That such crosses were ornamental clamps is evident from the shield of Helie, Comte de Maine, engraved in Montfaucon’s Monarchie Française. In Glover’s roll we find “John Lamplowe, Argent ung crois sable FLORETTE,” the ex-ample is here given from the coat of Robert de Lamplowe, temp. Edward I.

The Cross PATONCÉE is sometimes called PATEE, and occasionally confounded with FLEURY.

“William de Vesci, goules a ung croix PATONCEE d’argent.” Glover’s Roll. The example is here given from the seal of William de Vesci, A.D. 1220.

The Cross PATTÉE. “Le Comte d’Aumerle de goules ung croix PÂTE de verre.” – Glover’s Roll. Here is an instance that the cross patoncée was called pattée in the thirteenth century, as the arms of William de Fortibus Earl of Albemarle, temp. Henry III, are still extant, both in the embroidery and sculpture of the period, and the cross in every instance of the shape termed patoncée. Query, who is in error, the scribe or the artist ?

The term patté is derived from the Latin pateo, to be spread, and is applied to a cross, the limbs of which are broadest at their extremities. This sort of cross is discernible on the standard of King Stephen. The indenting of its terminations may have originated in a caprice, and been subsequently designated by a term derived from the same root.

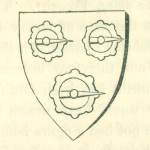

The Cross MOLINE, MILL-RIND, or FER DE MOULIN, is a term given to a cross with bi-parted and convoluted terminations, like the cruciform pieces of iron upon a millstone. “Azure, a cross MOLINE or,” are the armes parlantes of the noble family of DE MOLINES or MOLYNEUX, Earl of Sefton; and in the Roll of Edward the First’s time we have the subjoined example of the coat of GUY FERRE, “Gules, a FER DE MOULIN, argent, over all a bendlet, azure.” The modes of representing the cross moline, or mill-rind, are endless.

The Cross FOURCHÉE (Cruz furcata, John of Guildford) seems to me but a variety of it. The term occurs in Glover’s Roll, in which there is no mention of a cross moline, “Gilbert de la Val de la Marche, d’argent, ung croix FOURCHE, de goules.” Upton differs from John of Guildford in his notion of the figures.

The Cross BOTTONÉE, (Cruz nodulata, John of Guildford), sometimes called TREFLÉE, from its trefoil terminations is another fanciful variety of the cross fleury, and appears on the shield of Richard de Clare Earl of Hertford 1259-1262. Vide drawing of his seal, Cotton. MS. Julius C. 7.

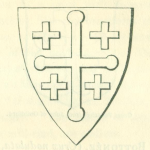

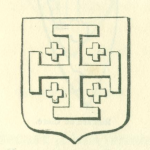

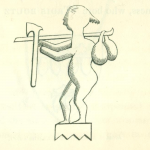

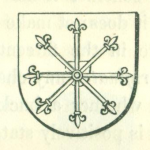

The Cross POMEL, POMETÉE or BOURDONÉE, terminating in single knobs or pomels, like the Bourdon, or Pilgrim’s staff. The example here given is from an early one of the arms of Jerusalem as a Christian kingdom.

To these varieties I may add

The Cross POTENT, so called because it is crutchshaped at each extremity, as in later examples of the arms of the kingdom of Jerusalem, Argent, a cross POTENT between four crosslets Or, (a departure from the rule prohibiting metal being placed on metal.)

The Cross CROSSLET or crossed, is another variety sometimes borne singly as a charge, but more generally in numbers. See more of the Cross Crosslet under DIFFERENCES.

The Cross VOIDED, sometimes called CLECHÉE, from some fancied resemblance to a key, is simply outlined, showing the colour or metal of the field. In Glover’s Roll such a cross is called FAUX CROI S or false Cross. “Hamon Crevecoeur d’Or ung FAULX CROIS de goules.

The list of comparatively modern varieties of this ordinary is almost interminable, and the confusion created by difference of opinion amongst heraldic writers as to their proper appellation, would encrease the tediousness of their enumeration. Edmondson, under Cross, has no less than 107 articles. Even old Leigh exclaims in his proper person to his imaginary instructor; “You bring in so many crosses, and of so sundry fashions, that you make me in a maner werye of them.” Before you are weary of them, Reader, if you be not so already, I will proceed to the second ordinary.

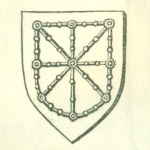

THE SALTIRE or ST. ANDREW’S CROSS.

A specimen of this ordinary is also to be found on the shield of one of the chess-men before mentioned. It is composed of four pieces of metal banded together and interlacing each other in the centre. The word SALTIRE is derived from the French Sautoir, in the old Norman orthography, Saultoir. The explanation of Upton, that it was an engine to take wild beasts, is only so far justified that a gate of that form was used to prevent the egress of deer or cattle.6

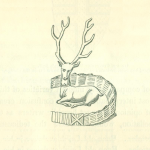

This gate is apparent in the badge of Richard II, of the hart lodged in a park, in the sepulchral slab of Thomas de Mowbray Duke of Norfolk, discovered at Venice, 1839, and engraved in the Archteologia, vol. 29. “In fact,” says Menestrier, “a wood and a park were formerly called des Saults, and in latin Saltus.” In an ancient MS., temp. Edward I, respecting tournaments, a squire is forbidden to have a “sautour” to his saddle. (Harleian, No. 6149). Menestrier quotes the same passage from a French copy of “Ordonnances, MS. des Anciens Tournois,” and adds an extract from the accounts of Etienne de la Fontaine, argentier du Roi, 1352, to prove that sautoirs, made of silk cords, were appended to the saddles of the knights, “qui leur servoit à sauter sur leurs chevaux.” In a note on this subject in my paper on Armorial Bearings, (Transact. of British Archaeological Association, 2nd Annual Congress, Winchester, August, 1845), I have added, “It is singular that we should meet with no pictorial example of this custom.” Can we have met with one in the seal of Patrick Dunbar, Earl of March, engraved in Mr. Laing’s beautiful and valuable volume of Scottish Seals, Edinb. 1850, Plate 13 ?

The noble family of Nevil, Earls of Westmoreland and Warwick, bore gules a SALTIRE argent from the commencement of the thirteenth century. Geoffrey, son and heir of Robert Fitz-Maldred by Isabel de Nevil, in consequence of the great possessions of his mother, assumed the name of her family, but retained the arms of his own, derived, according to tradition, from his great-grandfather, Cospatrick, Earl of Northumberland. It has been suggested that the Nevils assumed the Saltire on being appointed Wardens of the King’s Forests throughout England. But the rolls of Henry III’s time do not support this otherwise probable derivation. For Hugh de Nevil, who was made warder by king John in the third year of his reign, was called Grossus and the Forester, and died in the sixth year of the reign of Henry III, was succeeded by his son John, also Warden, and in Glover’s roll we find him as “John de Nevill le Forrestier,” bearing “d’or ung bende de goules croissettes noir.” Another “John de Neville,” termed “cowerde,” bearing the old Nevil coat of mascule “d’or et de goules,” with “ung quartier de hermyne,” and “Robert de Nevill,” son and heir of the aforesaid Geoffrey, the arms in question “de goules ou ung SALTIER d’argent.” This Robert de Nevil was however warden of the king’s forests north of Trent, and died in 1281, vitâ patris.

Tradition may, notwithstanding, be correct in this instance, for although Cospatrick died in 1070, a century before the general usage of coat-armour, crosses so disposed, but of irregular forms, are seen on many of the shields in the Bayeux Tapestry, and a saltire has always been appropriated to St. Patrick as well as to St. Andrew. It may consequently have been retained by his descendants as their cognoissance, or assumed by them at a later period in commemoration of him. The discovery of some earlier authority than Glover’s roll can alone settle this point. Our example is taken from the roll, temp. Edward I, and I beg you to observe the narrowness of the bars.

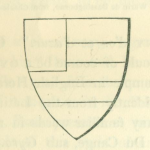

THE CHIEF is the upper portion of the shield, by modern heralds limited to exactly a third part of it. Its name is derived from the French chef, signifying simply the head or uppermost portion of the shield. Imagine pages written to account for this extraordinary appellation! “William de Fortz (Fortibus) de Vivonia d’argent a CHEF de goules.”- Glover’s Roll. A chief charged with a saltire is to be seen upon a shield of the Lewis Chess-men, and an early seal of one of the Clinton family supplies us with an example previously to the chief being charged with stars or fleurs de lis: a fleur de lis being, in the present instance, placed above the whole shield, as a badge or ornament.

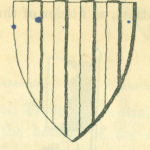

THE PALE (Pal, French) is a straight band or stripe, from the top to the bottom of the shield, occupying, according to modern rule, one third of the middle portion, but much narrower in ancient specimens, as indeed are all the ordinaries, except when they are charged. The term is familiar to us in the pales or paling of a garden or park.

The shield of the equestrian figure on the seal of “Rogerus de Fraxineto (Roger de Ashe) Regis Constabularius “displays a PALE, though the curve of the shield prevents our seeing the entire width of it, and the arms of Hugh de Grentmesnil, Lord of Hinckley, Lord High Steward of England, temp. Henry I, are said to have been “gules a PALE or,” the red shield having been strengthened most likely by a perpendicular bar of metal, gilt for ornament. The arms of the honour of Hinckley are well known to have been “party per PALE indented argent and gules:” witness the banner carried by Simon de Montfort, as holder of that honour.

Modern Heraldry has introduced the PALLET and the ENDORSE, as diminutives of the PALE. When the shield is divided into several equal portions, perpendicularly, it is said to be PALY of so many pieces, as “PALY of six, or and gules,” for Eleanor of Provence, queen of Henry III, vide example of that period from Westminster Abbey.

The BEND (Bande, French) is a similar band crossing the shield diagonally from the right to the left. When it is drawn in the opposite direction, from left to right, it is now called in England “a BEND SINISTER,” but in the fourteenth century it was called a FISSURE. Menestrier calls it a BAR, and a diminution of it is in this country commonly called “the Bastard’s Bar.” (See MARKS OF ILLEGITIMACY.)

Richard Foliott is said, in Glover’s roll, to have borne “de goulz ung BENDE d’argent.” The seal of Peter de Mauley (” Petrus de Malolacu “) affixed to the Barons’ letter gives us an example of the bend, in this instance slightly embowed to mark the curve of the shield; the field is diapered with scroll-work. The bends figured in Charles’s Roll, temp. Henry III, (Harleian MS. 6,589) are in a great many instances curved like the one before us. The bend was anciently used as a difference as well as an original bearing. See under MARKS OF CADENCY.7

The BENDLET, BENDIL, or little bend, describes itself. In the book of St. Albans we read, “on the same manner of wise are borne litel bendys as here it shall be shewyt, and they be called bendyllys, to the differens of great bendys, as it is opyn.” When one of these little bends was placed on each side of a great bend, it was called a COST or a COTTICE (from costa, Latin, a rib, côte, French) as in the well-known arms of the De Bohuns, Earls of Hereford. “Le Comte de Hereford, azure six Lioncels d’or ov ung BENDE d’argent a deux COTISES d’or”.-Glover’s Roll.

A field divided into a number of parts, bendwise, is called BENDY, as “Piers de Montford, BENDÉ d’or et d’azure.” – Glover’s Roll.

The same division made the contrary way is called “BENDY SINISTER.”

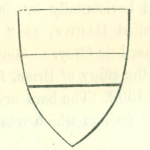

The FESS, so called from the Latin fascia, French face, “hath been taken of old,” according to Leigh, “for a girdle of honor, occupying the third part of the field, in the middest, between equal parts.” Now if it did contain in breadth the third part of the shield, it could not resemble a girdle at all: but the breadth of all these ordinaries appears, “of old,” to have been perfectly without regulation, and the Fess, especially in early specimens, is frequently drawn so narrow that modern heralds would call it a Bar, or even a Barrulet, the diminutive of a Bar. For which reason, perhaps, some French writers make no difference between the Fess and the Bar, whilst others, Menestrier for instance, as I have just told you, apply the term Bar to the Bend Sinister. In England, the BAR is considered by some writers as a separate ordinary, and, according to modern regulations, should not exceed the fifth part of the shield: but I am inclined to believe it but a diminutive of the Fess, if indeed it be not identical with it; made wider only when it was charged with one or more figures. It is worthy of remark that neither John of Guildford nor Upton mention the term FESS, but it occurs continually in Glover’s Roll, as well as that of BAR, “Walter de Colville, d’or ung FECE de goulz.”

“Richard de Harecourt, d’or a deux BARRES de goules.”

THE BAR never occurring singly however, strengthens my opinion that it was a diminutive of the FESS, as

The BARRULET is of the BAR. It appears to me, that when a Fess or Bar was accompanied by narrower bars, the latter were naturally so distinguished in blazon; as thus, in Upton, “Portat unum BARRUM et duas BARRULAS de Niger in campo argento. Il porte d’argent ung BARRE et deux BARRULETTES de sable,” and in the book of St. Albans we find actually, “he beareth asure oon BAR and ij LITILL BARRIS floresht of silver.” It is sometimes called a BRACELET, and a still narrower bar a CLOSET.

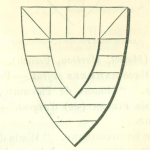

A field divided horizontally into a certain number of equal parts is called BARRY, as “BARRY d’argent et d’azure,” for Richard de Grey. – Glover’s Roll. Here is an example from the effigy of Brian, Lord Fitzalan of Bedale, who died in 1302. The bars are not flat but ridged down the centre, a fashion which was revived in the sixteenth century.

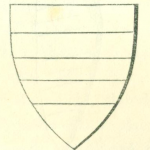

BURELY or BARRULY, signifying a similar division, but in a greater number of pieces.

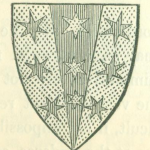

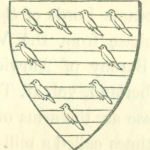

Our example is from the shield of arms of Aymer, or Ethelmar de Lezinghem or Lusignan, Bishop of Winchester, on his monument in Winchester Cathedral. He was the brother of William de Lezinghem, Earl of Pembroke, who assumed the name of Valence and differenced his arms with an orle of martlets. “William de Valens BURELÉE d’argent et d’azure ung urle dez merolts de goules.”- Glover’s Roll. (Vide under ORLE.)

BARRY BENDY is the division of a field, both by horizontal and diagonal lines, or bar-wise and bend-wise, the tinctures being alternated or counter-changed as it is called. This term of BARRY BENDY is given also by Upton to BARRY PILY, that is to say, where the diagonal lime does not cross, but only meets the horizontal one at the edge of the shield, thereby forming figures something resembling the PILE placed bar-wise; but when PILES are actually so placed, the proper term is PILY -BARRY.

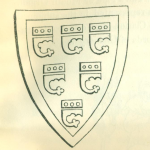

BARS-GEMELS, is a term given to very narrow bars (BARRULETS or CLOSETS) placed in couples, whence their name, from the Latin, gemellus double. In Glover’s Roll we find “Robert de Tregoz de goules a trois GEMELES d’or, ung Lion en chief, passant, de goules,” (? or) but in Charles’ Roll, the arms of Tregoz are drawn with two bars gemels, not three, and they are so blazoned in the Rolls of Edward II and III.

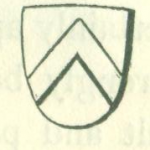

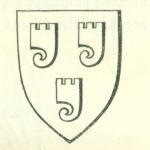

“The CHEVRON, says Leigh, “is the seventh honorable ordinary,” and he quotes Upton, who says that “a chevron is made of Carpenters, and is the highest part of the house, for the house is not finished until the chevron be set up,” and then Leigh adds, that “Carpenters call it at this day, the barge-couples,” and that “in the old time it was a certain attire for the heads of women priests!” Now the only sensible part of this story is that which Leigh has extracted from Upton, and which proves nothing more than that the term CHEVRON was applied, in the fifteenth century, to what are called barge-couples to this day, and are familiar to all persons who take delight in our fine old gable-ended houses. That the heraldic figure known as a CHEVRON, received its name from its similarity to that portion of a building is very probable. It was borne by the family of Tyeys or Teye, as “armes parlantes.”

To the Barons’ letter to the Pope, A.D. 1301, are affixed two seals; the first, of Henry Tyeys, displaying a chevron, and the second of Walter de Teye, a Fess charged with three mullets between two chevrons. A chevron is also borne by the German family of Sparre, such being its name in German, and in the Roll of Edward II’s time, (Cotton, Caligula A. XVIII,) we find “Sir Richard de Charoune de goules a une CHEVEROUN e iij eskallops de argent;” the jingle between Charoune and Cheveroune being quite sufficient to authorize the grant or assumption. But what was the origin of the figure itself? Fortunately the seal of a Clare,- the family to which most of our English nobility and gentry are indebted for their chevrons, – enables us to answer the question: it is that of Gilbert de Clare, Earl of Pembroke, in the reign of King Stephen, and therefore of the period which immediately preceded the bearing of hereditary coat-armour.

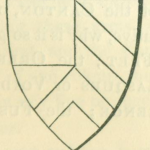

Instead of the three chevrons, so well known as the coat of Clare, we find the long kiteshaped shield of the Earl divided into thirteen equal stipes or bands, which running upwards parallel to the line formed by the angular top of the shield, (a very marked peculiarity in the shield of that period) on the dexter, or right-hand side, presented to us, descended, I naturally infer, with the slope of the shield, on the sinister or left hand side, and that such was the opinion of Bysshe is evident, as he blazons the arms, in Latin, thus “scutum capreolis plenum habuit,” considering them what is termed chevronny, that is, composed of as many chevrons as could be put, of that breadth, into the field. Now it certainly appears to me evident that this shield was only strongly banded according to its form, the bands being gilt and pointed alternately, and that their reduction to the number of three, in conformity with a prevailing fashion, produced the coat of arms which we see on the seals of the later Clares, viz. “Or, three CHEVRONS gules.” “Le Comte de Gloster, d’or a trois CHEVERONS de goulz,”-Glover’s Roll. “Moris de Barkele, goules ung CHEVRON d’argent.”- Ibid.

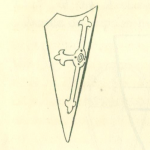

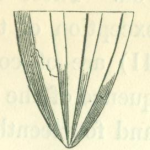

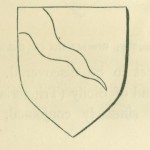

THE PILE is said by some writers to derive its name from the Latin, Pilum, a javelin or dart, by others, from the pointed piece of timber, called a pile, employed in the construction of bridges, &c. The French however call it simply, a point reversed, une pointe renversée, their Pointe being a pyramidical figure, which we might truly call a pile, in that sense of the word, which implies a conical heap, but which is by English Heralds sometimes called a pile transposed. It was borne singly by the family of the celebrated Sir John Chandos, “De argent a ung PEEL de goules e un label de azure,”- Roll of Edward II’s time, and a curious example of a difference of this coat appears in Charles’ Roll, temp. Henry III, where we find a Robert de Chandos bearing or a piles gules charged with three estoiles of the first (i. e. or) between six of the second (i. e. gules).

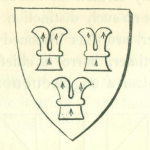

David, Earl of Huntingdon, and his son, John le Scot, Earl of Chester, bore or three piles meeting in base, gules. The example here given is from the seal of the latter. His sister, Devorgilia de Baliol, exhibits on her seal a shield with only two piles.

The QUARTER describes itself, being the upper right hand quarter or fourth part of the shield. “Bertram de Crioll d’or a deux cheverons et ung QUARTIER de goules.”- Glover’s Roll.

In Charles’s Roll a similar coat is given to “Robert d’ Waspail,” but it is remarkable that all the other coats blazoned with quarters in Glover’s Roll are, both in Charles’s Roll and in their seals, represented with what we should rather call a large CANTON, or diminutive of the Quarter; vide under CANTON, page 51.

All the above ordinaries, say the Heralds, may be charged, that is, may have armorial figures depicted on them; but their diminutives are not to be so honoured. They do not add the very excellent reason, that it would be exceedingly difficult, if not impossible, to charge some of them, as a glance at the endorse, cottice, closet, couple, close, &c. in any modem manual of heraldry will convince you. These said denominations, by the way, with the exception of the cottice (vide Arms of de Bohun, page 41) are of comparatively recent invention, the consequence of the vast increase of coats during the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries.

We now corne to the

SUBORDINATE ORDINARIES,

amongst which the quarter and the pile, before mentioned, are placed by some writers. They consist, according to others of the CANTON, or diminutive of the Quarter (if a diminutive, why is it so generally charged ?); the GYRON; the FRET; the ORLE; the TRESSURE; the FLANCHES, FLASQUES or VOIDERS, and according to some, the LOZENGE; the FUSIL,; the MASCLE, and the RUSTRE.

For all this classification, I can only repeat we possess no authority which can be considered decisive, and the want of concord amongst the Heralds themselves, must be my excuse for want of faith in any.

The CANTON occupies the dexter or right hand corner of the shield, and according to strict modern rule, should be about one-third of the chief. In the coat of Sutton, it forms a charge of itself, and the arms of a branch of the great family of Clare are said by some writers to have been “argent a CANTON gules,” but I have never been able to find a contemporary example.

The term occurs in Glover’s Roll: “Ernaud de Boys argent deux barres et ung CANTON goules.” In the well known coat of Woodville, the Canton is blended with the fess, argent a FESS and CANTON gules; and Leigh asserts, in blazoning these arms, as if from authority, that the Fess was first, and the Canton given in reward, adding that, being of one colour, they are not “purfelde,” i.e. not divided by any line or space; purfle signifying a hem, edge or border.

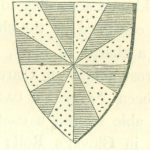

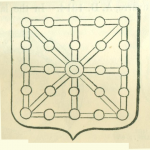

The GYRON is said to have been probably of Spanish origin, the word signifying a gusset or gore in that language. The division of the shield into irregular triangles, is called in English armory GYRONNY or GIRONNÉE, and an instance occurs in Glover’s Roll, “Warin de Bassingborne GERONY d’or et d’azur.”

One of these irregular triangles would of course be a GYRON, but I have not found an example in English Heraldry. The term has its origin evidently from the Latin gyrus, a circle, the root of so many familiar words in modern European languages, (vide Du Cange, sub Gyro.) The divisions formed in the figure of a wheel by the spokes are girons. The Italians have gherone, and Jerome de Bara says it was anciently called (in French) guyron, as though the g were harsh before the vowel, but John of Guildford calls this figure JERCONIS, in French, “Il porte d’argent et goul JERCONIS,” and places it under the head of “Armis inangulatis,” whilst Upton designates it “Arma Contra Conata,” but also uses the word GIRONE in another instance. The Spanish Family of GIRON bears GIRONNY or and gules.

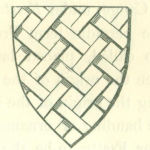

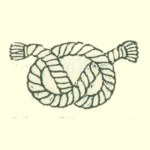

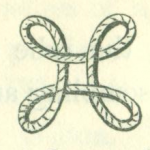

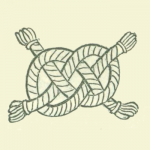

The FRET is a very ancient ornament; and garments, standards and horse furniture, previous to the appearance of Heraldic insignia, are often represented with that species of lattice work decoration, which was ultimately called FRETTY or FRETTÉE. “Item una tunica de samitto rubeo Frestata de auro cum rosulis aureis ad perlos.” See Du Cange, under Frestatus, and also under Frectee, where the heraldic term Fret is derived from Fretes, arrows, so called, placed lattice-wise. Whatever may have been the origin of the word, there can be no doubt respecting the origin of the bearing, which was evidently from the banding or ornamenting of the shield. I therefore consider Fretty to be the earliest form of the charge.

The shield of a chess-man, engraved by Mr. Shaw in his “Dress and Decorations of the Middle Ages,” from the original in the Cabinet of Antiquities in the Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris, presents us with a very early example of this style of ornament; it is said to be of the time of Charlemagne, but I should scarcely give it so early a date. It appears to me to be of the end of the eleventh or beginning of the twelfth century: early enough for our purpose.

In Glover’s Roll there are ten examples, all Fretée. The Harrington family, deriving their name from the sea ports of Harrington or Herrington in Cumberland, bear sable a fret argent, and from this example (perhaps one of the earliest) the charge is sometimes called a Harrington Knot. If however the coat of Harrington is an allusive one, as it has been stated, and intended to represent a fishing-net, it is most probable that originally it was Fretty like those of Verdon, Mal-travers, &c. and subsequently reduced to the single Fret.

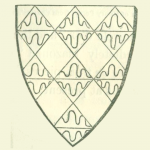

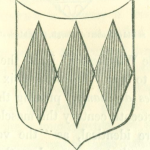

The same observation will apply to the LOZENGE, the MASCLE and the RUSTRE. The instances of such charges being borne singly are all of comparatively modern date. The original coats are LOZENGY or MASCULY. The RUSTRE is merely a lozenge or mascle “pierced of the field,” as it is called, that is to say, having a circular hole in the centre, through which the colour or metal of the field is seen. A shield divided by single diagonal lines, crossing each other at regulated distances, forming a diamond pattern, is called Lo – ZENGY; when the compartments are alternately filled with metal and colours, one of these diamonds or lozenges “voided of the field,” that is, having the centre cut out to within a certain ‘distance of the edges, becomes a mascle, from macula, the mesh of a net, and the joining of these by the angles, produce the charge called MASCULY, which, if carried completely to the outer edge of the shield, could scarcely be distinguished from Fretty; the difference consisting in the latter being composed of interlaced bands, and the former of flat plates: but in Glover’s Roll we find no mention of Lozenges or Lozengy. The coat which is now so blazoned, of Fitzwilliam, is with others termed Masculy. “Richard de Rokele, MASCULEY d’ermyn et de goulz. Thomas le Fitzwilliam port mesme.” “Le Comte de Kent (Hubert de Burgh) MASCULÉE de veree et de goules.”

“Le Conte de Winchester,” is, in the same document, said to bear “de goules a six MASCLES d’or voydes du champ,” proving thereby that in the thirteenth century the mascle and the lozenge were identical, as “the voiding of the field “constitutes now-a-days the only difference between them.

The FUSIL is an elongated lozenge, so called from its resemblance to a spindle (fuseau, French), but it does not appear in Glover’s Roll. The arms of Perey, well known in after times as “azure five FUSILS in FESS or” is there given as a fess engrailed.

“Henry de Percy d’azure a la fesse engrele d’or,” and the arms of Montague follow almost immediately blazoned “d’argent avec ung fesse engrele de goules de trois pieces,” instead of “argent three FUSILS gules,” as at present.

The elongation of the points of the engrailed fess, until they became three Fusils, may have been a caprice in the latter instance, suggested by the name Mont-aigu or Monte-acuto; but in the case of Percy, we have the curious fact, that in the third year of Edward II, A.D. 1310, the Percys became Lords of Spindleton near Bambourough, by purchase from the Vescys, from whom also they had the Barony of Alnwicke. Vide Wallis’s Antiq. of Northumberland, vol. II. Testa de Neville, &c.

Three fusils in fesse are the arms of Trefusis.

The fusil is sometimes called a mill-pike or pick.

John of Guildford and Upton name all three charges, and the latter distinguishes them by stating the fusil as longer and narrower than the mascle, and that, whilst the mascle can be placed in bend or otherwise, the lozenge must always be perpendicular.

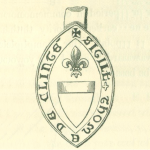

The ORLE, so named from the French, ourler to hem, is a species of border detached from the edge of the shield; but in early rolls it is called a false escutcheon, faux escochon, or in other terms, an escucheon voided of the field, i.e. the centre portion cut out, as in the case of the mascle before mentioned. “John de Balliol, de goules oue ung faux escochon d’argent.”-Glover’s Roll.

Birds and other charges are sometimes arranged in Orle, as the Martlets in the arms of De Valence.

Modern armorists confine the number of things so placed to eight, unless specially enumerated.

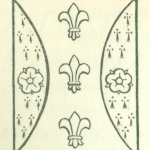

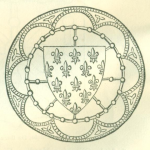

The TRESSURE has been regarded as a diminutive of the Orle, and is a similar border, only narrower, and borne double, sometimes triple, and generally what is termed flory-counter-flory, as in the arms of Scotland.

The origin of the Tressure, by the way, in the said Royal Achievement, has caused dreadful inkshed. It has been gravely asserted that it was granted by Charlemagne to the Scottish king in token of ancient alliance. If so, his successors were sadly ungrateful to the Emperor, for the Tressure is not to be found enclosing the lion rampant before the reign of Alexander III. Vide seal in Laing’s Descript. Cat. Plate I, Fig. 1. Jerome de Bara calls the double tressure “deux filects.”- Blazon des Armoiries, p. 49.

The FLANCHES, FLASQUES and VOIDERS may be quickly dismissed: they are of no great antiquity, and signify a larger or smaller proportion of the sides of the shield when it is divided saltier-wise: the flanks, in plain English. The figures are formed however by curvilinear lines, and may have been suggested by a peculiar garment in fashion during the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, the name of which has not yet been ascertained. These charges are always borne in pairs, and voiders form part of the augmentation granted by Henry VIII to Queen Katharine Howard.

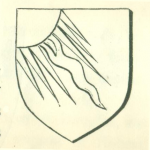

To return to the principal ordinaries: – six of these give their names to the various single lines used in dividing the field of the escutcheon, when more than one metal or colour is displayed, such escutcheon being described as parted, or party per pale, when divided perpendicularly; per fess, when horizontally; per cross, when in four squares; per saltire, when in four angles; per bend, dexter or sinister, when diagonally, from the right or from the left; and per chevron, when in the shape of that figure. The chief being itself formed by a single line, they do not say party per chief; but when the partition line is not strait or even, its peculiarity must be specified, as must also the outline of any ordinary under the same circumstances. There are but three irregular lines mentioned in Glover’s Roll, viz:

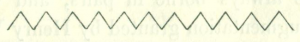

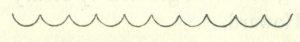

- Undée (ondée) or wavy,

- Engrailed, and

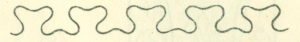

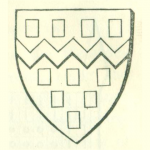

- Indented or Dancettée.

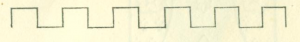

Later heralds have added three more: Invecked (the exact converse of Engrailed), Nebulée, and Embattled.

| 1 | Indented. | |

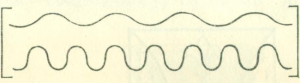

| 2 | Engrailed. | |

| 3 | Undée (two modes). | |

| 4 | Nebulée. | |

| 5 | Embattled. | |

| 6 | Invecked. |

The arms of Robert de Ufford, from a roll temp. Edward I, exhibits a cross ENGRAILED.

A seal appended to the Barons’ letter, A. D. 1301, exhibits three bars UNDÉE.

The banner carried by Simon de Montfort, (page 39 ante,) is an early specimen of indenting.

“John D’Eyncourt azure ung DANSE et billety d’or,”

i.e. a fess DANCETTE, as it would now be blazoned; but in early heraldry a Danse is often blazoned as if it were a distinct ordinary, and the terms, indented, engrailed and fusilly are most capriciously confounded.

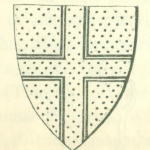

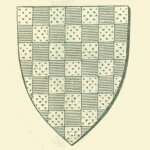

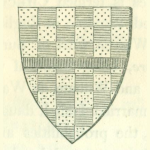

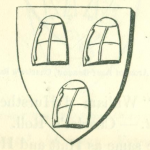

The division of the shield into an unlimited number of small squares by transverse perpendicular and horizontal even lines is termed CHECQUY, and the most early and celebrated example in English Heraldry is found in the coat of Warren, Earl of Surrey. This coat, checquy or and azure, being identical with that of Vermandois in France; and William de Warren, second Earl of Surrey, having married Isabel, daughter of Hugh, Earl of Vermandois, the probabilities are certainly in favour of its having been assumed by the Warrens in consequence of that alliance. Checquering, however, is a decoration of so simple and obvious a character that it is found in all countries and at all periods, and the armorial bearing may after all be no more than the perpetuation of a merely fanciful ornament. Vide Standard checked and spotted, from a Spanish MS. A. D. 1109.

The coat of Clifford is also checquy or and azure, but differenced with a bend or a fess, according to the Branch.

Both bend and fess are so narrow in the ancient examples that they are, by some modern writers, called a bendlet and a barrulet. The widening of them was evidently occasioned by the necessity of placing charges upon them; in the instance of the bend, three lions or, and in that of the fess, three leopards’ heads or, or three roses argent.

Having spoken of the principal figures which may be called purely heraldic, we will proceed to those charges which represent

NATURAL AND ARTIFICIAL OBJECTS

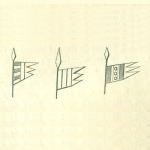

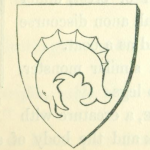

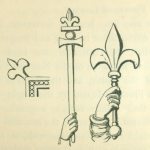

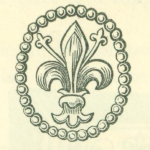

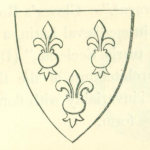

Amongst the earliest of these, the Lion, the Fleur-de-lys and the Eagle are the most numerous, being the symbols assumed by the sovereigns of England, France and Germany, for reasons which will be hereafter examined, and consequently borne with some alteration of colour or position, by all who could claim kindred or connection, however distant, with royalty. To these were added Griffins, Swallows, Martlets, Wheatsheaves, Crescents, Stars, Roundlets, Annulets, and a variety of objects familiar to the Pilgrim and the Crusader, such as Water-budgets, Cockle-shells, Bezants, Palmers’-staves, Helmets, Swords, Battle-axes, Arrow-heads, &c., as well as hundreds of others, the names of which bore affinity more or less in sound to those of the Titles, Domains or Families of the bearers. These were again granted to, or imitated by, the holders of property under their original assumers, until it became a work of considerable ingenuity to compose a coat of arms which should escape challenge by a previous possessor. At first these various objects were borne singly, or they were repeated ad libitum, and in any position, according to the fancy of the owner, or in compliance with the shape of the shield; but it soon became necessary to determine strictly their number, and to consider one more or one less a distinct coat – nay to account the slightest difference of attitude in an animate, or of position in an inanimate, object, a sufficient alteration. From the regulations arising out of this obvious and imperative necessity sprung the system of heraldry, which we get the first glimpse of in the rolls of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries; and from the establishment of certain officers to frame and enforce them, we may date the commencement of those fanciful theories, and perhaps intentional mystification, which, promulgated with a view to exalt the science, have contributed mainly to its degradation. Learned men, the early Heralds most probably were, I may say, unfortunately, for the learning of that day was so adulterated by superstition, that the grosser the legend, the more greedily it was swallowed. The self-deluded alchemist and astrologer, the credulous chronicler and naturalist, contributed their wildest dreams and most absurd deductions to the general stock of error,- more fatal from the classical foundation that invested it with a semblance of authority, and every fabulous property that has been attributed to animal, vegetable or mineral, every imaginary influence of the elements and the heavenly bodies, were pressed into the service of armorists to give a mystical or allegorical signification to the simplest and plainest of Charges. In the curious works Written in the twelfth century, by Theobald, Philippe du Than and Marbodius, Bishop of Rennes, on the natures of animals and the properties of precious stones, &c. are to be found “Fancies, which,” Mr. Sharon Turner remarks, “could have only pleased our ancestors, because, in the total vacuity of unlettered ignorance, any ideas, any reading, must be preferable to none.”8 “It seems to us,” says the same author, speaking of Du Than, “absurd for him to have hunted for allegorical meanings and religions applications which have really no greater connection with the animals he describes, than with a monkey or a potatoe.” Equally absurd was the practice of the Herald, but he had the same excuse Mr. Turner allows to the poet, who “wrote to please, and would not have so written, if it had not gratified the royal patroness (Alice, Queen of Henry I,) to whom he addressed it.”

Another great resource for the Herald was the continual importation of exaggerated stories of the marvels witnessed and the achievements performed in the plains of Palestine. Not content with the natural motive for displaying some symbol of faith or sign of pilgrimage, some extravagant legend, some miraculous appearance, was promulgated as the cause of the assumption. Hence the lamentable deficiency of credible authority for our present purpose; hence the difficulty of tracing to their true origin so many singular and interesting charges. We must reserve for special chapters the examination of the most important, and proceed to the classification of arms.

CLASSES OF ARMS.

The modern Heralds enumerate eleven classes of Arms namely of Dominion, Pretension, Community, Assumption, Patronage, Succession, Alliance, Adoption, Concession, Paternal or Hereditary, and Canting or Allusive Arms; but anciently they could be divided simply into two: -Arms of Assumption, and Arms of Concession.

ASSUMPTIVE ARMS

are now described to be such as a man assumes of his proper right, without the approbation of his sovereign and of the King of Arms; but in the dawn of heraldry all arms were assumptive. Every leader, whether king or knight, assumed a device according to his fancy, or by which he might be most readily distinguished in the field. Such in the course of time became arms of Dominion, Pretension, Community, Patronage, Succession and Alliance.

ARMS OF CONCESSION

are now explained, augmentations granted by the Sovereign of part of his ensigns or regalia to such persons as he pleaseth to honour therewith. But anciently not only sovereigns, but every feudal chief granted or conceded a portion of their own armorial bearings to favoured followers in battle, or holders of land under them.

Both these classes naturally became Hereditary or Paternal arms, and as to Canting or Allusive coats, nothing but the utter ignorance of later writers of the first principles of the science they professed to illustrate, could have given rise to the invidious distinction. It is scarcely possible to find an ancient coat that was not originally canting or allusive (that is to say, alluding to the name, estate or profession of the bearer), excepting, of course, those displaying simply the honourable ordinaries, which, as I have already stated, took their rise from the ornamental strengthenings of the shield, and even these were occasionally so. As I shall have numberless opportunities of proving this fact, I will only quote at present the words of the learned and reverend Father Marc Gilbert de Varrenes, who, in the section of his work devoted to “Armes Parlantes,” observes, “If according to the maxims and practice of all sages, which ordain that we should, in the first place, ascertain the means by which we are most likely to arrive at our end, we take into consideration the mark at which aims the entire usage of shields of arms, I hold myself assured that in a few hours we shall change our minds, and instead of the contempt usually bestowed upon Canting arms, we shall acknowledge they deserve to be greatly esteemed for their simplicity. For as all armories were invented only to make distinctions between persons, and enabling us to discern one from another, serve as a particular mark of everything belonging to us, certainly nothing can be more conducive to this effect, than to cause ourselves to be known by the animal or the article which has the same name that we have.” Le Roy d’Armes, Paris, 1540.

And at page 469, he says, “This opinion derives its probability from the fact that our ancestors, less curious and more simple than we are at present, usually took care in the composition of their arms that there should be a correspondence between their names and the figures with which they emblazoned their shields: which they did, namely to this end, that all sorts of persons, intelligent or ignorant, citizens or countrymen, should recognize easily and without further inquiry, to whom the lands or the houses belonged wherever they found them as soon as they had cast their eyes upon the escutcheons.”